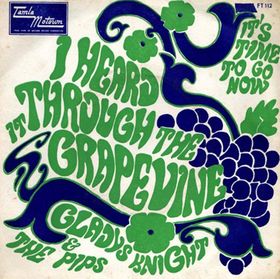

Gladys Knight and the Pips – “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” Pop # 2, R&B # 1

By Joel Francis

Unlike nearly every other soul singer at the time, Gladys Knight didn’t want to go to Motown. She was (rightly) worried she and her group, the Pips, would end up playing second fiddle to Diana Ross and the Supremes. However, the Pips were a democracy. When the rest of the group voted to migrate to Hitsville, Knight reluctantly acquiesced.

“I Heard It Through the Grapevine” was a thrice-heated leftover when Norman Whitfield presented his song to the group in 1967. Smokey Robinson and the Miracles cut a version the previous year that didn’t make it out of Berry Gordy’s Quality Control meeting. A second Miracles recording of “Grapevine” was buried as an album cut on 1968’s “Special Occasion” LP. The Isley Brothers were rumored to have recorded a version during their brief stint on the label, but no recording has surfaced to date. Several Motown scholars believe a recording session with the Isleys to cut “Grapevine” was scheduled, but then cancelled.

This is likely the case. In 2005, Motown released the two-disc clearinghouse “Motown Sings Motown Treasures.” This incredible and enlightening collection presented many recordings – Kim Weston performing “Stop! In the Name of Love,” the Supremes doing “Can IGet A Witness,” and the Miracles original, unissued version of “Grapevine,” among others – previously locked in the vaults. It seems unlikely that the Isley Bros. version of “Grapevine,” if it exists, would have been omitted from this collection.

Although it wouldn’t be released for another year, Marvin Gaye had also cut his reading of “Grapevine” by the time the Pips were hearing Whitfield’s pitch.

Whitfield’s latest “Grapevine” arrangement was inspired by Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” and Whitfield’s desire to “out-funk” Franklin. It’s clear from the great snare-and-cymbal intro that Whitfield was on to something new. Motown had been a lot of things until that point, but it had rarely been so overtly funky. In the coming years, Whitfield would help place Hitsville at the epicenter of psychedelic soul. This recording was one of the first steps down that path.

Whitfield’s attempt to out-do the Memphis soul sound Aretha was getting from Atlantic producer Jerry Wexler was buoyed by Knight’s singing. The gospel background isn’t as obvious in Knight’s delivery, and her voice is a little earthier than Franklin’s, but Knight’s vocals can soar just as high. In fact, the song is little more than drums, piano and Knight’s powerful voice until a scratch guitar enters during the first chorus.

Stealing a page from the Holland-Dozier-Holland production book, the tambourine is mixed front and center. The instrument serves as a tractor, dragging the entire song it its wake. The signature organ line that introduces Gaye’s chart-topping “Grapevine” makes a cameo on the piano about a minute into the song. The saxophone solo bisecting the song is a straight-up homage to King Curtis, the Memphis soul legend. Even the juiciest gossip is rarely this much fun.

The fourth time was the charm for Whitfield, as the Pips’ powerful “Grapevine” finally made it past Gordy’s Quality Control meeting. That didn’t guarantee label support, though, as Knight was forced to rely on her DJ connections to promote the song. When “Grapevine” finally caught on, it caught fire holding the top spot on the R&B chart for six weeks and stalling behind the Monkee’s “Daydream Believer” at No. 2 on the pop chart. Although it was Motown’s best-selling single to date, the “Grapevine” story was far from over.