Sweet times, sweet sounds at 18th and Vine

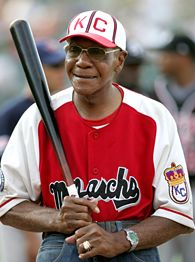

An Interview With Buck O’Neil

By Joel Francis

(Note: This 1998 interview was published in 2001 by The Independence Examiner newspaper.)

Q: I’d like to talk about the jazz scene in Kansas City, be cause you talked a little bit about that in your book, and I think that’s an exciting aspect of our town that people may not hear about as much, especially when they think of you. What was Kansas City like in the 1930s and ’40s?

A: Outstanding. See, Kansas City was a wide-open town and all the restaurants would have live music hotels would have live music, bars live music, and so it became easy to get a gig here. So musicians flocked here and played. Kansas City was a town that closed up at 1 o’clock (a.m.), at least the legitimate places. And so the musicians would flock to this area (18th and Vine) and we had a place called the Subway.

All the musicians would come after they got through working and, oh, they would jam all night, have jam sessions, yeah. You wouldn’t be surprised to see Basie there, or Joe Taylor, Georgia Thomas and musicians from all over the country. You would see them down there at this thing jammin’, just having a good time they were having a good time. Or Charlie Parker would drop in, or a blues singer maybe Big Joe Turner, somebody would drop in. All of these things were happening here, just a couple blocks from here; (it was) very alive.

Q: You were obviously a big part of the baseball scene. Why were baseball and jazz so closely linked together?

A: We played the same circuit, man. We’d go to Chicago to play. We’d be playin’ on the South Side and they would visit our ball games and we would go to the jazz joints. It was the same thing, not only there, also in New York City. We would play ball in the afternoon, say Sunday afternoon in New York City, Sunday night go down to Sugar Ray’s, the Apollo we were catchin’ all the acts there or the Baby Grand. All of this live music, it was just jazz. They were playin’ jazz all over. We did this at all of the places we would play. At matinee shows all of the theaters had bands. In Harlem, like I said, we would go to the matinee and maybe we would catch Cab Calloway, see? And we would go from there to Washington, D.C., and the Howard Theater. Maybe Ma Mabley was there and we would catch her, or Duke Ellington, or Fletcher Henderson. Everyplace that we went to play, the jazz people went, too. This was during the days of segregation, so we probably stayed at the same places, and we got to know them and they knew us.

Q: How would you describe the Kansas City style of jazz?

A: Exciting. Different. It was different that New Orleans. And right out of Kansas City, we come up with Charlie Parker, blowin’ notes nobody’d heard before. This is a brand new thing! These were the kind of things you could hear at that Subway. Here come a new dude, come in blowin’ something you hadn’t heard before a different note. Where did this come from? Where did this sound come from? It was a brand new sound.

And the good thing about it was that the musician was telling a story and it was his story to tell. They were playing the same song, but when it was his turn to come up and blow, it was different. And you could see the other musicians listening and coming in, you know. This drummer’s going to change the beat now. He’s got to change that. You could hear it if you’re listening; you could hear the change. This guy’s playin’ “Ain’t Misbehavin'” a little different than the other guy did. He’s puttin’ a little something of him in there. You could listen to a new story. The guy would blow notes, you knew who it was without seeing him, you know what I mean? You knew it was Armstrong. You didn’t have to be in there. You knew it was Ben Webster. You knew all these things. A little jazz. So many things were happening all over the country.

Q: Like what?

A: The music was live and the whole country (was) changing. A top musician would go to, maybe, Paris and when he came back from Paris, this was his style, but he had picked up something else. Or he might go to Egypt Cairo, or something like that. And here was a guy doing something on the bongos that was just different than they were doing in Harlem. You added a little something to what you were doing. You would take a little of this, a little of that.

And the jazz singers (did this with their) different phrasing styles. Like, nobody phrased like Billie Holiday. She could just open her mouth and hey, that’s Billie. You knew because nobody did it like Billie. You could hear the different phrasing and all of it was so clean, so clear.

This is the only thing I have against a lot of the things they play now. It’s hard to understand, because a lot of the words, the way they’re sayin’ them, I don’t get. But they were so clear. Like the tones they were playin’. The tones were so clear, you could hear it, you knew it; you weren’t confused. I like rap. I like to hear rap if the guy is distinct and I can understand what he’s saying. But if he jumbles it all together where I can’t understand it, it ain’t good. This is why music then, anyone who sang it, (sang) a clear note. You could understand it. You like to know what they’re doing and where they’re going from there. They will lead you around through this thing if you listen. Music is a great medium.

Q: What role did Tom Pendergast and his political machine play in the development of jazz in Kansas City?

A: It provided a place for them to play it was a job. It was in that era they had the speakeasy they had everything goin’ on and you had to provide entertainment with it.

Q: So did Pendergast turn a blind eye to it?

A: No. If there was a blind eye, it may have been the government turning a blind eye to Pendergast. There wasn’t anything illegal about jazz, but the things Pendergast was doing could have been illegal.

Q: Did any of Pendergast’s illegal activities help the jazz scene grow?

A: It just may have, because you know you’ve got to entertain the people you’re selling whiskey to, or the people going to gamble. Right now, we’ve got the boats, and gambling is legal. Whereas it wasn’t legal during that day and you had to entertain people. This was good entertainment.

Q: If speakeasies were illegal, how did people know where to go to hear the music?

A: Pendergast was running the city. When you say illegal, if I am the boss of the city and I am running the city this way, it wouldn’t be illegal. What would have been against the law was this: If you were running a club and instead of closing at 1 o’clock, you stayed open ’till 3 o’clock. If you stayed open at 3, you were doing the same things at 3 you were doing at 10, but the law was you had to close at this time. And the places would close, the musicians would come down here and go into that Subway and play and jam. And somebody down there would be doing something illegal, because somebody would be selling some whiskey. A lot of these things were happening before prohibition.

Q: So did Prohibition help the jazz scene?

A: Yeah, sure. Actually it opened it up all over the country. Wherein you had to go just to certain spots before, now you’re (playing) in Manhattan, you’re playing in Times Square. You’re playing now all over the country, even going to universities to play. Before you were playing in speakeasies, but now you’re playing in clubs.

Q: What were some of the hot jazz clubs in Kansas City at that time?

A: The Milton was strictly jazz. They had so many different clubs in Kansas City and … music was everywhere. During that time, just like a band comes to the Starlight and plays now, every weekend it was some band at the Municipal Audi torium. That doesn’t just mean Count Basie or something like that, but Benny Goodman would play; everybody would come. I’ve seen so many wonderful bands down there.

Q: What are some of your favorite bands you’ve seen play there?

A: I like Duke. To really jump I like Lionel Hampton. I was a very good friend of Count Basie; I like Basie. I like Goodman. The Jazz Philharmonic that was the top musicians put together and they traveled all over the country. Oh man, you talk about some music! You’d hear these great artists play. I like Armstrong. They had a girl band called the Sweethearts of Rhythm; they could play. First of all you were going because it was a girl band and you wanted to see them, but they could play.

There was another one called Tiny Davis. She blew that trumpet Louis Armstrong-style; she could play. Bob Burnside played the sax he could play the bell off of that horn! It was the era of the Mills Brothers. They were one of the first singing groups, the Platters and a whole lot of others came behind them.

Q: I couldn’t go too far in this interview without mentioning Satchel Paige.

A: He was an outstanding athlete.

Q: What did Satchel think of the jazz scene?

A: He loved it. He used to play the ukulele. He would play on the bus and we would sing along. Satchel Paige, yeah, we had a lot of fun.

Q: Did Satchel go with you to all the concerts at Municipal?

A: Yes, yes he would go. We all would go as a team. They (jazz musicians) would come out to the ball game in the afternoon and at night we would go down to the jazz concert. That was a couple of musts. If you lived in Kansas City, it was a must on Sunday afternoon to go to the Monarchs and see baseball, and it was a must after that to go to the Municipal Auditorium and hear these bands.

Q: Did they ever bring any of the Monarchs onstage and introduce them as celebrities?

A: Actually they would introduce the teams, because if we were playing the Chicago American Giants here, they would be going too. All of us would be there.

Q: Did both teams sit together?

A: Sometimes.

Q: What did your managers think about the jazz scene?

A: They were there. What do you mean “what did they think,” they were with us! (Laughs).

Q: Did they impose any rules about drinking and things like that?

A: You knew that yourself. You knew you couldn’t drink too much. We were there, but we didn’t drink that much. Everybody drank a little maybe, but you didn’t drink that much because you knew you had to play ball the next day.

Q: I’d like to name off some jazz performers and have you tell me some memories about them. A lot of these we have mentioned already. Let’s start with Bennie Moten.

A: Bennie Moten, that was early. That’s when I first met Count. Count was playin’ with Bennie Moten. A good musician.

Q: Lionel Hampton.

A: I made him first base coach for the Monarchs. It was just for a show. They were playing here that night and I put him in a uniform. His wife said that he kept that uniform and had it on an easel he kept in one room. He would tell everybody about that uniform.

Q: Count Basie.

A: Basie was a Yankee fan, and I’m a Dodger fan, see. And we would bet every year on the Yankees and Dodgers. You know he beat me most of the time, but we had a lot of fun.

Q: Duke Ellington.

A: Duke was sophisticated and clean. Clean music. Like with Lio nel, you wanted to dance, Duke you wanted to listen.

Q: Charlie Parker.

A: Oh, now you got a new step. You could start dancin’ a different way because you got a different beat. Charlie, he used to blow here at that Subway. He’d drop in as a kid, blowin’ that horn, making those new sounds.

Q: How did his death at such a young age affect you?

A: It wasn’t too much of a shock because of the way he was going. You knew the things happening to him, so it wasn’t a shock.

Q: Louis Armstrong.

A: That was music you could listen to, and you could laugh with Louie because Louie had a kind of a laughing horn, you know. When he blew that horn you’d laugh about the different notes he’d play. The thing about it is, you know that handkerchief he had to cover up so nobody was coppin’ those things. Quite a fella. Baseball nut too; he liked baseball.

Q: What was Satchmo’s favorite team?

A: It would be, more or less, the Black Yankees.

Q: What do you think caused the decline in the jazz scene in Kansas City?

A: It’s coming back now, and that’s all over the country. Different listeners are coming and they’re looking for new sounds. This is our last progress in anything and it’s something new, something different.

Q: What does jazz mean to you?

A: It has afforded me a lot of pleasure. I listen to it now and I like all music. There’s something about music. With television, I have to look, but I can do anything I want to do and listen to music. Every once and awhile somebody’s going to hit a note or something and I’m going to stop and listen to what they’re playing. Music can put me to sleep at night or it can wake me up. It’s a soothing thing, but it can be very exciting too.