“This too shall pass, I’m gonna pray

Right now all I got’s this lonesome day”

By Joel Francis

I didn’t make it to Bruce Springsteen’s concert at the Sprint Center Sunday night. Around the time he was going onstage – about 8:50 – most of my extended family was leaving the hospital. It had been a long day. Grandma started aspirating about noon, and for the third time that week we all descended upon her intensive care room. At 10:30, about the time Bruce was ripping into “Spirit in the Night,” the nurse told us Grandma’s heart was working harder because her oxygen levels were falling. It didn’t look good. The nurse said it was unlikely Grandma would survive the night.

“Hard times baby, well they come to tell us all

Sure as the tickin’ of the clock on the wall

Sure as the turnin’ of the night into day

Your smile girl, brings the mornin’ light to my eyes

Lifts away the blues when I rise

I hope that you’re coming to stay”

Even before he took the stage, Springsteen was my release. My wife and I saw him last March in Omaha, so we didn’t buy tickets when this show was announced. Even so, the possibility of grabbing tickets from a scalper just before showtime was always open. I even bought a pair of earplugs to the hospital with me, just in case. I pulled them out of my pocket every so often and wondered “Where would the band eat dinner?” Knowing this was the final concert of the tour I imagined how long they’d play. “Hey,” I’d say to no one in particular, “what song are they going to open with?” or, later, “What song do you think they are playing right now?”

“A dream of life comes to me

Like a catfish dancin’ on the end of the line”

Helen Kelley was born in Minneapolis in 1920. The sixth of seven children, she met my grandpa at church. After Grandpa returned from World War II they moved to Manhattan, Kan. where he attended Kansas State on the G.I. Bill. After earning his doctor of veterinary medicine the couple and their young daughter, my mother, relocated to Independence, Mo., where he opened a pet hospital on 23rd Street.

My favorite memories of Grandma take place in the children’s clothing store she opened next door to Grandpa’s pet hospital. Ostensibly hired to help with inventory, she grew to appreciate the Beatles, B.B. King and Ray Charles CDs I brought along. We would talk for hours, solving all the world’s problems before taking the obligatory break for “Oprah.”

“I got a picture of you in my locket

I keep it close to my heart

A light shining in my breast

Leading me through the dark

Seven days, seven candles

In my window light your way

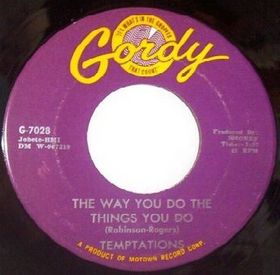

Your favorite record’s on the turntable

I drop the needle and pray”

On the trips back and forth from the hospital in the week leading up to Grandma’s death Springsteen was my passenger. The titles alone were testimonies: “Reason to Believe,” “Counting on a Miracle,” “Land of Hope and Dreams,” “Waitin’ on a Sunny Day,” “The Promised Land,” “Lift Me Up,” “Lonesome Day.”

We finally left the hospital Sunday night after Grandma’s condition had plateaued and we had collected promises of a phone call if anything changed. As we sailed up U.S. 71 I rolled down the windows and gave the speakers a workout. “Rosalita,” “Backstreets” and “Thunder Road” from the 1975 Hammersmith Odeon concert. When we arrived at the house around midnight, the E Street Band was finally leaving the Sprint Center stage after a three-hour marathon set.

“May your strength give us strength

May your faith give us faith

May your hope give us hope

May your love give us love”

Grandma died shortly after 8 p.m. Monday. Her family huddled around the hospital bed and sang the old hymns she loved so much. I doubt she heard them, but if she did, one of the last sounds Grandma would have heard was “Jacob’s Ladder.” This 19th century hymn has its origins in the slave churches, but was popularized by Paul Robeson in the 1920s and Pete Seeger in the 1950s. Springsteen recorded it on his “Seeger Sessions” album. Another of Grandma’s favorite hymns came from those same sessions.

I got into Springsteen too late to share him with Grandma, but I think she would have enjoyed him. If not, she would see how happy his songs made me and gamely smile along. As I made my final trip home from the hospital, I knew Grandma was enjoying the Boss’ performance of “How Can I Keep From Singing.”

“My life flows on in endless song

Above earth’s lamentation…

No storm can shake my inmost calm

While to that rock I’m clinging.

Since love is lord of Heaven and earth

How can I keep from singing?”