By Joel Francis

The Daily Record

Author Elijah Wald has dedicated his past two books to stripping away the legend and mythology surrounding two of music’s most iconic figures, and placing them in the context of their times. In “Escaping the Delta,” Wald demonstrates how Robert Johnson was very much a product of his time, and how his deification was established. Wald’s latest book expands that motif, and bears the inflammatory title “How the Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll.”

Wald recently took the time to speak with The Daily Record about some of the themes in his new book and, of course, how the Beatles changed rock and roll.

In the book you talk about how “everything old becomes new again,” and use the Twist to illustrate your point. What are some of the other examples of cyclical trends you discovered?

To be fair, I don’t say everything old can always be recycled. When something new comes along, we tend to look back and find things that seem similar to us. But I think that may be less a recognition of real cycles than a way of making the present seem less strange.

Clearly, things come back, but when they do come back they are different. I’m not sure things are cyclical. It may just be they way we get comfortable with them. When the Twist came around, the way the entertainment industry handled it was to talk with Irene Castle and say “This is like what was happening in 1914, isn’t it?”

Why do you call “Rhapsody in Blue” the “Sgt. Pepper’s” of the ‘20s?

This is really the germ of the whole book. I was reading how people in the people in the 1920s wrote about “Rhapsody in Blue” and noticed how similar it was to what was said about “Sgt. Pepper’s” in the 1960s.

(In the 1920s) everyone was saying how until now jazz was a lot of noise and music for rowdies and kids, but now this had turned it into a mature art form. This is exactly what happened with “Sgt. Pepper’s.” Leonard Bernstein said he was excited about it and Lennon and McCartney were compared to Schubert. Just as “Rhapsody in Blue” created a respectable thing that could still be called “jazz,” “Sgt. Pepper’s” created something respectable that was still considered rock.

Who was Paul Whiteman and what was his impact on music? Why has he largely been forgotten today?

I spend a whole chapter in the book on this, but in a nutshell, Paul Whiteman was the most popular bandleader of the 1920s. He was the man who transformed the perception of jazz from noisy, small groups into large orchestras who played not only fun dance music, but also at Carnegie Hall.

I think Whiteman is largely forgotten because he didn’t swing by and large and was resolutely white. We have understood the history of jazz to largely be a history of African-American music. Whiteman tried, for better or worse, to separate jazz from that heritage.

In many ways, the 1940s parallel today, in that there is fear new technology will usurp the traditional way artists got paid. Then it was a fear of jukeboxes and radio’s reliance on pre-recorded music and today, of course, the dominant issue is digital piracy. What are some of the similarities and differences you’ve observed between these two decades?

The huge difference is that all the things we talked about in the ‘40s did involve musicians getting paid, just different musicians. It was R&B and country musicians getting paid instead of big bands. A lot of people previously neglected became huge stars.

What’s happening now is really dangerous, in terms of musicians continuing to be able to make a living. It is exciting, in terms of everyone being able to make their music available to millions of listeners, but it is getting harder and harder to make a living in music. It’s more like a lottery – win and become a star or lose and go on to something else.

There are skills you develop as a professional musician that we’re seeing less and less of because people don’t perform as much. Everyone in my book went through an apprenticeship playing seven nights a week for four or five hours a night. Those opportunities no longer exist. There’s no way to build those kinds of skills today.

Explain the difference between hot and sweet combos. Why have the hot survived while the sweet are dismissed?

A lot of people will say this is a false dichotomy. Everyone played some sweet and some hot, but the best way to explain the difference to people of my generation is to go back to the British Invasion. In the U.S., we thought of both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones as belonging to the same genre. In England, however, the Beatles were called pop and the Rolling Stones were called R&B, and it’s easy to understand why.

The way we look at it today, hot bands played for boys who were into music as fans and listeners, while sweet bands were for sappy girls. That’s not the way I would phrase it, but it’s not necessarily wrong. Women have always been the determining pop buyers, because they like to dance, but men have always been the main critics. In any case, in the 1930s the two extremes were Guy Lombardo on the sweet end and Count Basie as hot, but most bands were in the middle.

One reason the hot bands live on is because by and large the only people listening today are jazz fans and they always liked the hot bands better. There’s also the racial component I mentioned earlier. I don’t disagree that what is exciting in American music was largely taken from African-American music—I would argue that it’s more complicated than that, because they are always interchanging, but as a listener I am certainly more excited by Basie than by Lombardo. As a historian, though, I am interested in both, and well aware that in their era Lombardo was far more popular.

What is the connection between swing and rock and roll?

What is the connection between swing and rock and roll?

It was the hot dance music, youthful, noisy dance music. We think of these worlds as separate, but a lot of the same musicians crossed over. The first house band for Alan Freed’s rock party was the Count Basie Orchestra. Bill Haley and the Comets all did their apprenticeships playing swing. Musically, there was a lot of overlap.

How did the success of the Beatles and other late-‘60s rock bands segregate the music industry? What are the lasting effects of that segregation?

Two things happened at once. One, the Beatles arrived when the industry was moving very heavily toward black music. The myth is the Beatles rescued us from Frankie Avalon, but they really rescued us from Motown and girl groups. If you look at the charts, black groups had so completely taken over, they actually stopped having separate charts.

The Beatles and British Invasion bands were exciting, but their rhythm sections were old fashioned. In a world of Motown and James Brown they played archaic styles. Black kids were not much interested in the British bands, because they weren’t as much fun to dance to—and it was not just black kids, but everyone who was dancing to Motown, which included a lot of white kids, especially white girls.

At the same time, the discotheque craze was hitting, so people didn’t have to have live bands. The lasting effect of that is that you no longer had to have one band who could play every style of music. Before you couldn’t have a band play only black or white music, because people wanted to dance to and hear the full range of current hits. In the ‘60s, though, you could have one band only play one kind of music, because when you wanted to hear a different kind you could just change the record.

In the epilogue you discuss how rock and dance music gradually began playing to divergent audiences. Do you think they will intersect again?

Today we don’t have bands that have to play anything, period. It’s a sad reality that if you listen to hit records – or even records that aren’t hits, by little-known, local performers – the number of records where the group on the album plays regularly is vanishingly small. The number of hits that can be recreated without recordings is virtually none.

Don’t get me wrong; hip hop couldn’t exist in a world where you had to play everything live and I think hip hop is exciting. Overall, however, the world of live music is becoming extinct. There are certainly plenty of people for whom live music is important, and I’m sure there always will be, but they are increasingly a minority.

Keep reading:

Review – “How the Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll”

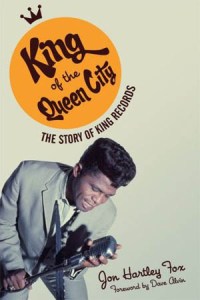

Talking King Records with author Jon Hartley Fox

Review – “King of the Queen City”